Votre panier est actuellement vide !

A light born from the living – Toward bio-inspired and circular fabrication

What if the end of one cycle could become the beginning of another?

Our project was born from this simple question, driven by a deep conviction: nature already holds the answers to today’s major challenges. In a world saturated with synthetic materials and centralized production, we chose to look toward the living, the local, and the invisible threads that connect all things — mycelium.

This project is a collective experiment at the intersection of design, biology, and the circular economy. It brings together four entities with complementary expertise: Esser Studio, a textile design studio and initiator of the project; échofab, a Fab Lab specialized in sustainable design; Mycélium Remédium mycotechnologie, experts in mycelial metrology; and the key actor Ganoderma lucidum — the mycelium itself, a master of carbon-chain decomposition, a terraformer, and thus, a regenerator of life.

Together, we envisioned a symbolic object — a chandelier — made from scraps: textile offcuts, mushroom farm residues, and mineral aggregates. Through a local, ethical, and distributed production chain, this project proves that it is possible to transform our waste into precious material, and to grow an object rather than extract or manufacture it. This object is, in truth, a superfood capsule for flora and fauna.

This chandelier is not just an object: it is a manifesto. A tangible proof that another way of producing is possible — one that is beautiful, biodegradable, and deeply rooted in place. We must help nature so that it, in turn, may help us reconnect humanity to the biosphere.

Core issue

Our project sits at the crossroads of four urgent and interconnected issues that call for a deep transformation of our systems of production, consumption, habitation, and relationship with the living world. It offers a tangible response to the management of textile waste, the valorization of underused organic flows, the imperative to relocalize production in urban environments so they may become more resilient ecosystems, and the need to reconnect with natural cycles — especially those of fungi, those discreet engineers of life.

First

The issue of textile waste remains a blind spot in our linear economy. From the very beginning of industrial cutting, up to 15% of textiles are lost as offcuts. These fragments, non- standardized, escape traditional recycling or recovery channels. Added to these are end-of-life textiles, too damaged or worn to be reused. Canada alone produces more than half a million tons of textile waste each year, less than 15% of which is recovered. These materials, though rich, are incinerated or land filled, when they could nourish new forms of local production.

Second

mushroom farms, which produce a valuable food resource, leave behind mountains of organic residue. For every 250 kilos of harvested mushrooms, 1 ton of mycelial substrate becomes waste. Some farms generate up to 6 tons per week of this still-active material. Though considered « spent, » these blocks are often composted. Yet they offer a malleable, biodegradable structure, ready for a new cycle of use — in design, architecture, and sustainable materials.

Third

Our land-use model is based on a deep imbalance: cities consume, rural areas produce. This extractive model, inherited from the industrial era, depletes rural environments while robbing cities of their creative capacity. In the spirit of Fab City, we must break this dependency. The key is to rethink our model toward localized production and renewed, regenerative resource supplies. This means designing autonomous, sustainable production chains modeled after natural ecosystems. It’s not about producing everything locally, but about recognizing that certain resources, once present on-site, should be transformed and used in situ. “Locality” then becomes functional: what is nearby must be activated where it is needed, to reduce footprints and increase resilience.

Finally

a fourth issue — often overlooked but essential — concerns our relationship to the living, especially to fungi. Millions of years ago, certain fungi evolved to decompose carbon chains on the Earth’s surface. These lineages became the great terraformers of our ecosystems — regenerating soil, nourishing flora, filtering toxins. But today, our urban environments are hostile to them: concrete, asphalt, and hygienism limit their action. Each fungal species has its own growth preferences, just as each human has their own tastes and needs. If we help nature, we allow these organisms to play their regenerative role once again — offering soils, fauna, and even us humans their incredible gifts: enzymes, nutrients, purification.

This is precisely what our project seeks to demonstrate: by merging textile scraps with locally recovered mycelial substrates, we create a hybrid material — biodegradable and moldable — to craft useful, aesthetic objects without extracting new resources. This local loop closes part of the production cycle, while experimenting with a future in which cities become factories of regenerative matter.

The project — A Light born from the living

It all begins with a simple gesture: gathering what industry leaves behind. Mushroom farm residues — at the end of their cycle yet still carrying life — and textile scraps from garment production, too small to be repaired, too precious to be forgotten.

These marginal materials are the beating heart of our project. We sought to offer them one last breath — not as waste, but as resource. To do so, we chose an everyday object, simple yet full of meaning: the chandelier. It embodies light, gathering, care. For us, it became a material manifesto — tangible proof that another way of producing is not only possible, but necessary.

We envisioned a local, distributed, and regenerative chain of creation, woven together by the complementary strengths of our group. Our goal: to help nature ful fill its purpose.

Collaborators

Esser Studio

Founded by designer Marie-Christine Fortier, Esser Studio is a textile design atelier based in Montréal, dedicated to ethical and sustainable creation. She is the initiator of the project and the visionary behind the concept of the mycelium chandelier. Esser transforms offcuts from its own collections into creative resources and pushes the boundaries of circular design by integrating living materials into decorative objects.

échofab

Digital Fabrication Workshop created by Communautique échofab is a pioneering digital fabrication laboratory rooted in social innovation and committed to democratizing technology. Specializing in distributed design and open technologies, the fab lab enabled the creation of molds using 3D printing and thermoforming, repurposing industrial plastic residues from the pandemic era into tools adapted to the cultivation of mycelium. échofab also ensures the alignment of the project with Fab City principles for localized, decentralized production.

Mycélium Remédium

Based in Montréal, Mycélium Remédium Mycotechnologies is an emerging player in the field of fungal biotechnology. Specializing in the cultivation and application of mycelium, it provides fungal strains and technical expertise for transforming substrates into solid, usable objects. Its role is essential in the development of protocols for growing, managing, and drying the mycelium.

Ganoderma Lucidum

The Reishi Mycelium – Invisible yet fundamental, the Reishi mycelium (Ganoderma lucidum) is the living heart of this project. This medicinal mushroom, renowned for its adaptogenic properties, forms a dense, strong, and resilient network. Fed with organic substrates, it digests, binds, and transforms matter into durable structures. Reishi is not merely a material — it is a biological ally, a natural intelligence at the service of regenerative design. Thanks to it, the chandelier comes to life, bearing a new kind of light — one rooted in the living.

Rooted in the spirit of Communautique’s living lab, our collaboration unfolded through exchange, exploration, and co-creation. Together, we cultivated an experimental fi eld where mycelium becomes a vector of living innovation, revealing what can emerge when humans and non-humans meet to generate new knowledge.

Creating homes

The starting point of our approach was a simple yet meaningful idea: to create a home for the mushroom. Esser Studio imagined an elegant chandelier shape, an everyday object transformed into a symbol of regeneration. Its minimalist aesthetic — with soft, calming lines — was designed to inspire serenity while subtly highlighting the living texture of mycelium.

This shape became the foundation for a co-creation process within the Fab Lab échofab. Using parametric 3D modeling software and a 3D printer, we translated this artistic vision into a tangible prototype, ready to host life.

The design evolved further thanks to the active involvement of all four project partners. Together, we adjusted the dimensions, openings, curves, and overall structure of the object to meet the speci fic needs of Ganoderma lucidum, a species known for its unique preferences in colonization speed, surface adherence, and ventilation. It was no longer just about designing a beautiful form, but about crafting a comfortable habitat — one that fosters growth, rest, and transformation.

Finally, using a thermoformer, we repurposed PET sheets leftover from the pandemic to mold two welcoming structures: translucent, protective homes made entirely from reclaimed materials.

Monitoring well-being

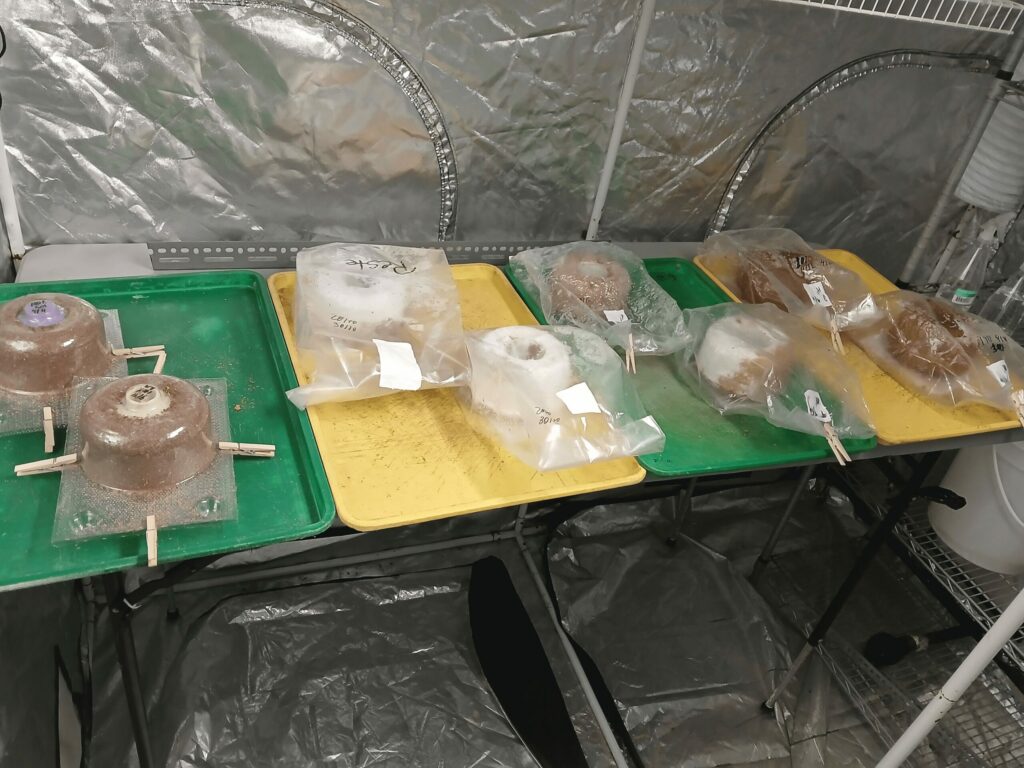

Mycélium Remédium Mycotechnologies developed a series of tailored substrate recipes to host the Reishi mushroom in an environment aligned with its preferences: dark, humid, and rich in the materials it loves to colonize. At the heart of these substrates lies a majority of organic matter sourced from mushroom farm waste — substrates “pre-digested” by other fungal species, rich in cellulose and lignin, ideal nourishment for Reishi. To this base, we added finely shredded textile offcuts from Esser Studio’s production.

By recreating this habitat through precise monitoring techniques — adjusting temperature, humidity, substrate density, and incubation time — we allowed Reishi not only to grow, but to truly inhabit the space and settle into it comfortably.

The recipes

The recipes are designed not only for the mushroom’s well-being but also for the material constraints of the final object. Mycelium is naturally very light and potentially flammable. To address this, we added aggregates such as recycled glass powder, which acts both as a flame retardant and as a weight balancer, as well as clay powder. Each recipe thus becomes a careful balance between care for the living and the demands of design.

These design requirements sometimes call for laboratory testing to validate the performance of the resulting material. The chandelier presented here remains a prototype that has not yet undergone full-scale testing to con firm, for instance, its level of flammability.

After two to three weeks, the mushroom finishes feeding. It then begins a phase of transition: with no nutrients left, it prepares to shift state — entering the stage of fruiting. This marks the end of the growth process and the beginning of a new use.

End-of-life care

In nature, the Reishi mushroom colonizes the inside of a tree trunk, slowly decomposing the wood for nourishment. Once satiated, it reaches the outer bark. There, the environment changes: more light, higher oxygen levels, lower carbon dioxide. This gaseous imbalance signals to the fungus — it’s time to stop seeking food and prepare for migration.

But in cities, that migration is futile: spores fall onto concrete or are trapped in ventilation systems. This is why we accompany Ganoderma lucidum through its final stage. Once removed from its home, it forms a protective mantle, ready to fruit. At this precise moment, we dehydrate it to a speci fic level. And thus ends its active cycle — this once-living matter becomes a precious capsule of superfood for flora and fauna.

Honoring the service rendered

The mycelium object we shape is not merely utilitarian — it is a testament to a service rendered by the living. In transforming forgotten waste into new resource, the Reishi mushroom offers us a material that is rich, fertile, and alive. To honor this action, we apply a natural nish that extends the lifespan of this superfood capsule, intended for the ecosystem.

We are experimenting with gentle solutions such as shellac, natural latex — which we hope to source locally from milkweed — and plant-based paints or starch-based inks. Each object is a celebration. A sincere act of recognition for this silent, patient transformation offered by nature.

The irregularities left by Ganoderma lucidum become signatures: marbling, spots, nuances, organic patterns. Each chandelier is unique. And each day we gaze upon it, we can say thank you — thank you to nature for its labor, its wisdom, and for reminding us that we are a part of it.

When its cycle is complete, the chandelier returns to the earth. Placed in a garden, on a lawn, even on contaminated soil, it nourishes plants, insects, and helps regenerate the land — allowing the mushroom to ful fill its role in the grand cycle of the living.

Next steps

This chandelier project stands as our proof of concept: a tangible demonstration that it is possible to create useful, beautiful, and meaningful objects from forgotten organic matter — in collaboration with living organisms like fungi.

This first success opens the door to broader research and development work. The supply chain derived from the living remains underestimated, yet it holds immense potential. Our next step is to streamline this process and design a flexible, adaptable manufacturing system tailored to diverse dormant resource streams. Nature always offers multiple solutions to a single challenge — let us draw inspiration from it to map and explore these overlooked materials: human-generated waste, organic residues, or long-existing discards that currently escape reuse systems but could nourish a variety of fungal species. By cultivating this diversity, the production chain could become a contributor to both biodiversity and functional needs.

We have also observed a distance: although people consume mushrooms, they rarely come into contact with living, transforming organisms. Industrialization has made standardization our norm — smooth forms, uniform colors, controlled textures. A tomato of irregular red becomes suspicious, a textured surface, a flaw. Yet nature does not conform to uniformity. It expresses itself through variation, through irregularities and nuances.

To respond to this, we aim to democratize a renewed relationship with life and with what is considered « normal. » Three paths emerge: first, citizen workshops to grow mycelium, enabling touch, observation, and cohabitation with living matter. Second, the creation of functional objects — chandeliers, ephemeral furniture, interior design materials — as sensory bridges between nature and everyday life. Lastly, using art as a vehicle for transformation, to shift perspectives and provoke awakening. Through these gestures, we hope to sow the seeds of a paradigm shift, where the unpredictability of life becomes beauty, not anomaly.

Perspectives & impacts

Community-led climate action

Citizen Engagement : Our project weaves together the knowledge of the living and human gestures to initiate a regenerative cohabitation between citizens, materials, and other forms of life. It calls for deep citizen engagement — not only between humans, but between species. We still have a long way to go in democratizing the presence of non-human actors in our habitats — fungi, bacteria, microfauna. This project offers a gentle encounter with an often-misunderstood organism: mycelium. Through objects with irregular forms, surprising textures, and non-standard colors, we invite humans to reconsider their relationship with the living in their everyday environments. It is about breaking the cultural fear of life within domestic spaces, and learning once again to coexist.

Policy & advocacy impact

In terms of public policy and advocacy, our approach is anchored in Fab City principles: reconnecting human production with the local biosphere. This project becomes a tool for raising awareness about a paradigm shift in design — moving away from an extractive logic toward a regenerative one, where each object becomes a message of feasibility, ecological inclusivity, and hope. It gives form to a localized production, where data, materials, and uses coexist in rhythm with life itself.

Community empowerment & capacity building

Lastly, this project contributes to a different kind of community empowerment — that of fungal and natural communities long marginalized in our urban systems. By giving them space to act — in our homes, our gardens, our soils — we allow them to reclaim their roles as terraformers, soil restorers, and silent engineers of ecosystems. Through their presence, a vast underground network of resilience comes back to life, in service of the living whole.

Sustainable tech & circular innovation

Technological innovation & design

Our project lies at the intersection of design, gentle biotechnology, and applied ecology. It explores the potential of distributed fabrication through the use of 3D printing, thermoforming, and co-cultivation with mycelium. Each tool is employed not to mass-produce, but to adapt to local resources, to the aesthetics of the living, and to the needs of the fungus itself. It is a form of slow technological innovation — one centered on listening to materials rather than dominating them.

Circularity & regenerative impact

In terms of circularity, our approach is firmly rooted in regeneration. We valorize two waste streams considered non-recoverable: textile offcuts from garment cutting and the “spent” substrates of mushroom farms. These materials, brought together in synergy, form the foundation of a new kind of living, biodegradable, and useful matter. Mycelium does not merely “replace” plastic — it activates a biological cycle that restores to matter an ecological function. It adds extra loops of life before reaching the end of its usefulness.

Scalability & practicality

This project is based on accessible technologies (fab labs, low-tech equipment, reclaimed materials) and on existing know-how from the world of mycology, which can be adapted to other types of waste and fungal species. The model is replicable by any urban community with minimal shared fabrication infrastructure, access to local waste, and mushroom farms — anywhere on the planet. The most delicate part is the dialogue between fungal strains and suitable environments. It requires a certain literacy of the living and, above all, close observation of results. In this way, it proposes a practical and evolving vision of symbiotic design, where each territory can adapt the object to its own materials, constraints, and cultures.

This chandelier is therefore not just an object: it is a proof of concept, a manifesto, and an educational tool for imagining a mode of production where nature and culture collaborate.

Regenerative ecosystems & biodiversity

Positive ecological impact

Our project is deeply rooted in an ecological regeneration approach, by giving new life to materials considered at their end. Each mycelium chandelier becomes a biodegradable capsule that, after its use, can be placed in a garden, a green space, or even on contaminated soil. Once exposed to the elements, it decomposes slowly and releases nutritional richness bene ficial to microorganisms, insects, plants, and local fungi — actively contributing to soil health and biodiversity.

Regenerative practices

The production cycle of this project does not merely aim to reduce its footprint — it seeks to give more back to nature than it takes. By incorporating textile waste, mushroom farm substrates, and natural but second-hand ingredients into our objects, we create active materials that continue to nourish living ecosystems even after their human use has ended.

Ecological Ssewardship

This is a matter of ethical responsibility toward the living — especially fungi, which play a crucial role in ecosystem resilience. By crafting “homes” that respect their preferences and highlighting the beauty of their presence through design, we are relearning how to collaborate with nature, rather than merely exploiting it.

Thus, our approach weaves together positive ecological impact, regenerative practice, and active care for ecosystems — proposing a model where each step, from conception to end of life, becomes an act of repair and gratitude toward the natural world.

Conclusion

Through this project, we wanted to demonstrate that a paradigm shift is not only possible — it is already underway. By growing an object rather than manufacturing it through traditional means, we shed light on a concrete alternative to extractive models: a regenerative approach rooted in the dynamics of the living. The mycelium chandelier thus becomes far more than an object — it is the fruit of an interspecies collaboration, a material proof that circularity and beauty can coexist, as long as we listen to and adapt to the rhythms of nature.

This project also allowed us to weave a local network of skills, materials, and knowledge, embodying the principles of distributed, ethical, and sustainable design. It shines a light on invisible resources — textile scraps, mycelial substrates — that, through gentle innovation and care for natural cycles, find new life.

Beyond the creation of an object, we have initiated a conversation: How can we give non-human organisms a place in our manufacturing processes? How do we honor their labor, their intelligence, and their regenerative potential? This light born from the living illuminates a future where humans no longer dominate, but cohabit. A future in which every object is a trace of gratitude toward the Earth, and every project a gesture of reconciliation with the living world

Marie-Christine Fortier

info@esserstudio.com

Annie Ferlatte

annie.ferlatte@communautique.quebec

Geoffroy Renaud

grg@champignons-maison.com